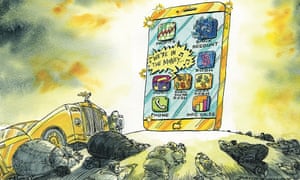

Apple lives on cream – the very top of the market. Researcher IDC says its larger-screened iPhone has pushed Samsung aside to hold a majority of the more expensive end of the market – devices costing more than $650. But it’s not just the phone cream that it has grabbed. After 30 years in the personal computer market, Apple has just recorded a historic sales high of 5.7 million Macs in a quarter. Like Stella Artois, Apple positions itself as reassuringly expensive; it is a top-end brand in markets that have mainly been commoditised, with profits drained from all but a few. Apple intends to remain one of the few.

Apple does not break out profits from phones, tablets or laptops, but industry estimates suggest operating margins of at least 28% for the iPhone, on its average price of $670. South Korea’s Samsung, the only other phone maker generating substantial profit, has just announced operating margins in its mobile division of 9%. Apple makes more than three times as much profit from iPhones as Samsungdoes from its mobiles. And the two companies account for all the profit there is in smartphones – LG, Sony, HTC, Microsoft and BlackBerry are all losing money on handsets. (China’s fast-growing Huawei, the third-biggest maker, has not announced any results.)

Similarly, in personal computers, Apple’s Macs have an average selling price of $1,205; most PCs sell for half that or less. At those prices, and with an estimated 18% operating margin, Apple made two-thirds of the $1.8bn profit made by the six biggest manufacturers in the second quarter of the year, but sold only 7% of the machines. The two biggest, Lenovo and HP, shipped 20% and 18% of PCs worldwide, and made 20% and 11% of the profits.

What is the secret? Advertising? Design? Lots of companies make products that look like Apple’s, and advertise them as heftily (in Samsung’s case, more so). It clearly goes deeper than that. Apple’s biggest stumble in the smartphone market was with the iPhone 5C, the “cheaper” device introduced in 2013 along with the pricier, fingerprint-reading 5S. Though the 5C was just the previous year’s iPhone5 in a plastic casing, it was clearly a cheaper option. Ben Thompson, who owns and runs consultancy Stratechery, says: “To buy a 5C was to show that you couldn’t afford a better one.” The lack of desirability meant the 5C was far from the big hit pundits had said a “cheaper iPhone” would be.

That need to be the desirable brand has prompted Apple to offer a $10,000 edition of its Watch. For a company that originally talked about making the “computer for the rest of us”, it seems odd to see it making a smartwatch for the 1%. Yet pricing is not a resistance point for Apple’s keenest buyers, and the Watch, despite its $350 starting price, is far outselling much cheaper devices from a range of rivals, again including Samsung, Sony and LG.

Thompson says that the iPhone in particular is here to stay – with more than 400 million in use worldwide. “Smartphones are the most important products in people’s lives, which means that the willingness to pay for the ‘best’ is higher than it is for just about anything else. The smartphone budget is likely to be the last to be cut in any sort of economic tightening.” And most iPhone users upgrade to another iPhone, he points out.

Overall, Apple may have wormed its way into the “affordable luxury” sector – taking its place alongside scotch whisky and nail polish in the pantheon of recession-proof items. In the end, it is not the price tag; it is how the product makes the owner feel.

“Across the board, our goal is to make the best in the categories we choose to compete in,” said Phil Schiller, Apple’s marketing chief, in an interview last week. “It’s what we’re doing and it’s reflected in customers choosing our products over anyone else’s. So I do think people are showing with their choice that they do value quality and beauty of the hardware, and that is not diminishing.”

Contents

Let’s hope the Fed won’t lose face over a rate rise

It has been a long wait for so-called “lift-off” in US interest rates, but now theFederal Reserve has sent a strong signal that the first hike in almost a decade will come before the year is out.

The central bank did so by dropping previous warnings about the fragility of the global economy in the statement it released alongside its latest decision to leave rates unchanged at near zero.

Fed chair Janet Yellen and her colleagues on the policy committee pointed towards the possibility of raising rates at their December meeting. It was a big gamble for a central bank that – like its UK counterpart – has got in a tangle with so-called “forward guidance” before. In September, financial markets were bracing for liftoff after the minutes to the Fed’s previous meeting, in July, had suggested policymakers were ready to push the button. Now here we are again with a clear steer that rates will rise in December.

The Fed may lift borrowing costs then, but with oil prices low and the global economy looking fragile, there are plenty of reasons why it may not deliver on its “guidance”. Figures last week showed US economic growth slowed sharply in the third quarter. Policymakers look forward, not back, but more timely indicators are not much brighter. There are still two more US jobs reports to come before the Fed’s December meeting, the first of which is published this week. Yellen and her fellow rate-setters had better hope it paints a stronger picture for employment and pay: because if they do not hike in December, the Fed will have a credibility problem.

Like a parent who makes empty threats or an “unreliable boyfriend” – to use one MP’s description of Bank of England governor Mark Carney – the US central bank has already seen its trustworthiness eroded this year. Its latest message may leave it looking like the central bank that cried wolf.

So policymakers will no doubt spend the runup to their meeting reminding markets that it is the economic data that counts. But it is going to be a sweaty six weeks.

Don’t play a numbers game. Women belong at the top

Sadly, after a five-year campaign to get more women into senior positions at the top of corporate life, there are still not enough of them. There are just eight more women holding executive director posts in the FTSE 100 than there were five years ago, when Lord Davies led his review for Vince Cable, then the business secretary. This means that women hold fewer than 10% of the executive seats at boardroom tables – proof that Davies’s target for 25% of the board to be female has been reached only by filling up the non-executive positions.

True, the days are gone when company bosses could get away with regarding their non-executives as baubles on Christmas trees (see Tiny Rowland of Lonrho) but the reality is that the real power lies with the executives. Davies has missed a trick.

Instead of raising his target for women in boardrooms to 33% and spreading it across the FTSE 350, he should have got tough. Go on: set a target for women in executive roles.

[Source:- The Gurdian]