When James Kassaga Arinaitwe first started working in international development, he focussed on global health. The motivations behind that choice were very personal — six members of his family had died from disease by the time he was 10 years old.

But in his native country of Uganda, he soon ran into problems that made him rethink his decision.

“I realised the foundations of everything were broken, because of a broken education system,” said Kassaga, who started Teach for Uganda alongside Charlotte I Nsengiyumva. We spoke in Bogota, Colombia, at a conference hosted by Teach for All, a global education network started 10 years ago as a collaboration between Teach For America, Teach First UK, and entrepreneurs who wanted to start their own branches in other countries (India and Chile, for example).

He continued:

I had set out to go into global health, but coming back, I realised there were no leaders in my community that had the wherewithal or the education that we needed to actually provide the healthcare that we need, or even the opportunity to fight [for it]…

If the people are not educated enough to know what their rights are, then how can you say we’re going to provide healthcare? I saw education as the basic foundation to even be able to know: ‘Oh, I can ask for health rights. Oh, we need a clinic in our community, and therefore my member of parliament should be advocating for that.’ Even immunisation, for example, you need to know why immunisation is important…

First we need to have a level of education where people actually know why healthcare is important.

His message was striking because it was urgent, self-apparent, and had been mostly overlooked by the Davos set.

It’s not entirely clear why the educational system hasn’t been central in the fretful post-Brexit conversations about (1) embattled public institutions, (2) labour-force skills mismatches, and (3) declining social trust.

Of course, if the World Bank’s 2018 World Development Report is any indication, education could work its way into the mainstream discussion soon. The organisation’s annual report focussed solely on education this year, for the first time since it started publishing the series back in 1978.

It argues that quality learning — not to be conflated with schooling — can help fix all three of the problems listed above. When it comes to social trust, for example, the report cites a 2015 OECD report that says the following:

Our analysis has demonstrated that education strengthens the cognitive and analytical capacities needed to develop, maintain, and (perhaps) restore trust in both close relationships as well as in anonymous others. It does so both directly, through building and reinforcing literacy and numeracy in individuals, and indirectly, through facilitating habits and reinforcing behaviours such as reading and writing at home and at work, which are also related to higher trust.

As for government institutions, it’s widely accepted that countries with better educational systems have higher political engagement. (While it’s fairly difficult to paint that in a negative light, this odd paper argues “political participation is more responsive to increases in individual schooling in countries with a higher per worker land endowment” because “the opportunity cost of the production income forgone from devoting more effort to political participation is lower in countries where human capital is less valuable in production activities.”)

Elsewhere in political economics, this handy 2012 analysis of the European Social Survey found that levels of education are correlated with trust in institutions — except for countries with high levels of corruption, where more education was correlated with mistrust. That’s a pretty compelling argument for education, unless you’re a corrupt politician.

Finally, the World Bank has some sharp words for those who spend time puzzling over the mismatch between the labour force’s skills and the job market without sparing a thought for their area’s school systems:

Work skill shortages are often discussed in a way that is disconnected from the debate on learning, but the two are parts of the same problem. Because education systems have not prepared workers adequately, many enter the labor force with inadequate skills.

Like Mr Kassaga’s story, the points above seem glaringly obvious when written plainly. And one conclusion that follows from all of this is that the benefits of education accrue to a wider group of people than just students.

So why isn’t global education more of a priority? And why do many academics treat the educational system as if years of school attendance were all that mattered, and quality were irrelevant? (Not all of them do, for what it’s worth — there’s been some interesting work on cognitive skills and economic development.)

One explanation is that, well, it’s just tough. Education is tied up in a knot of fraught social dynamics: it takes the significant (and growing) lifelong effects of childhood socio-economic status, adds in the historically heated topics of culture, language and identity, includes a dash of parental angst, and then steeps that mix in political disagreements.

It is also rather difficult to measure and isolate the broad benefits of quality education, especially on a global scale. Strong educational systems tend to exist in countries where the social contract is already robust — so the causality can be difficult to show.

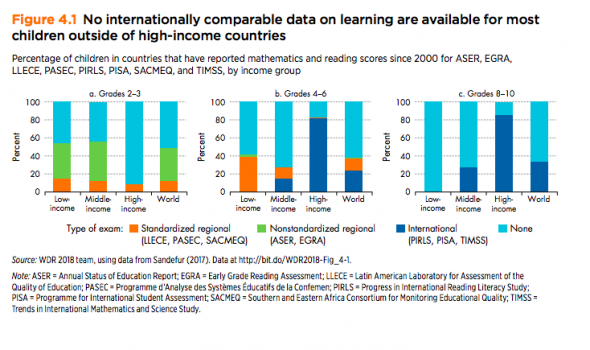

Another challenge is that the data just don’t exist in many places:

(As a side note, what is going on with the lack of second and third grade data for high-income countries above? There is plenty of strong academic work showing that early childhood intervention can have large effects, so that seems like it’d be kinda helpful for high-income countries to measure, right?)

From the development report:

Education systems routinely report on enrollment— but not on learning. Because learning is missing from official education management data, it is missing from the agendas of politicians and bureaucrats. This is evident in how politicians often talk about education only in terms of inputs—number of schools, number of teachers, teacher salaries, school grants— but rarely in terms of actual learning. Lack of data on learning means that governments can ignore or obscure the poor quality of education, especially for disadvantaged groups.

There are organisations — including Teach For All — that are trying to tackle this challenge. More on that soon.

Source:-ftalphaville