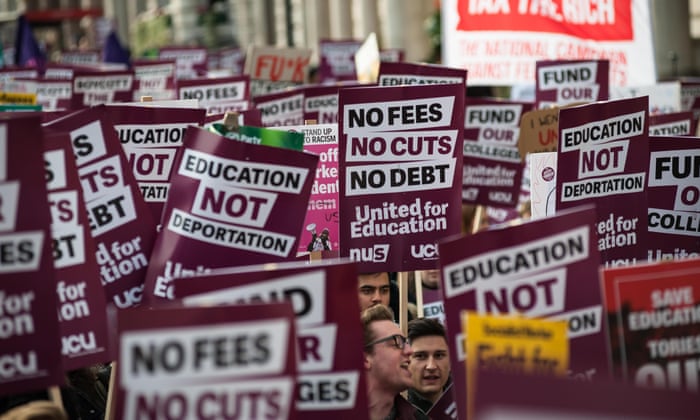

United for Education demonstration, in 2016. Universities are a big business now. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Universities have been so transformed by 30 years of reform that the language around higher education can appear emptied of its traditional meaning. The inherited notion of universities as a protected space devoted to the development of the individual capacity for creativity and deeper understanding has been hollowed out. In a world where students are consumers, who measure success by the class of their degree and their future earnings, the pursuit of knowledge is a marginal preoccupation. The experience of intellectual excitement that a good teacher can provoke is nothing compared with finding a job that justifies the accumulation of a vast debt. Universities are a big business now. International students are worth nearly £5bn a year in tuition fees alone, which is 14p in every pound of university income. Vice-chancellors can command salaries four times more than the prime minister’s and control budgets of hundreds of millions. They are the key to prosperity, students have become economic agents, and the dreaming spires have been replaced by the shiny glass headquarters of global knowledge corporations.

This transformation was radical, but it has allowed a huge increase in student numbers. Universities are rich; facilities have been upgraded. In some places, like Lincoln, they have unlocked dramatic economic regeneration. And until now the new regime completed by the Higher Education Act at least has had a certain internal coherence. Today, however, the question is whether this model can survive the consequences of Brexit and the Tory approach to it.

Universities face a triple whammy. The number of students from the UK is set to fall until 2020, and it won’t reach the levels of 2010 until 2027. Brexit threatens funding for research and collaborative ventures with EU academics, and high-quality research is critical to the world rankings. That could undermine Britain’s status as the home of more top-10 universities than any country except the US. Most threatening of all is Theresa May’s adamant refusal to take students out of immigration figures while cutting net migration to the tens of thousands. This year, applications from the EU dropped 7%. No wonder that after the boom years, some vice-chancellors are beginning to fear for their universities’ bank balances. A Deloitte survey in March found that nearly two-thirds of financial directors were less optimistic than a year ago, before the referendum, and less inclined to take risks. Their focus is on the student experience and attracting international students.

Just before the end of the parliament, the Higher Education and Research Actwas rushed onto the statute book. It was the culmination of the long road to the complete marketisation of the higher education sector; it smoothed the way towards more new, for-profit universities that will have the power to award degrees, provided they meet standards set by a new office for students. University autonomy is subject to providing value for money as assessed by a government quango. There will be a new rankings system, based on universities’ performance in a teacher excellence framework. This is intended to create a highly competitive environment that depends on the throughput of undergraduates. There will be casualties, but they are unlikely to come from the elite ranks of the Russell Group.

Labour’s big manifesto offer to abolish tuition fees and remove the burden of student debt is attractive; reintroducing the maintenance allowances is welcome. But in the short term, reinstating the teaching grant, according to the IFS, adds £11bn to the deficit. It is a bonus for graduates who get highly-paid jobs who won’t have to repay their loans, while graduates on lower incomes would be exempt anyway. And it might mean the reintroduction of a cap on numbers, which would work against widening access. Higher education deserves better than these ad hoc political fixes.

[“Source-theguardian”]