The subterranean world of catalogue rights is generating big bucks for traders and bands alike – no wonder a past-their-best punk group are willing to sign away the rights to their music

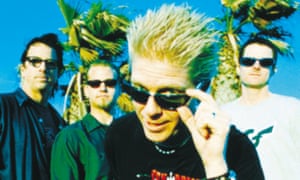

When was the last time you thought about the Offspring? Maybe when Pretty Fly (For a White Guy) topped the UK charts in 1999? Or maybe you followed them until their final UK hit, (Can’t Get My) Head Around You (No 48 in 2004). Perhaps you’re one of the loyal fans who bought their last album, Days Go By, in 2012, which peaked at No 12 in the US. Whatever your feelings about their music, however, it’s likely you no longer think of them as being one of the vital forces of the music industry, nor as one of the heritage acts guaranteed to generate money.

That doesn’t matter to the music rights company Round Hill Music, which has just paid a reported $35m (£24m) to the Offspring to acquire most of their rights. It now owns the rights to the group’s recordings for Columbia – six albums and a hits compilation – and the publishing rights to all nine of their albums, including the three they recorded for Epitaph, among them their biggest seller, Smash (though that is not included in the deal on recordings).

It feels as if it was not one but two lifetimes ago that the Offspring were the name on our lips. Why would anyone want to buy their catalogue? And, more to the point, why would they pay $35m for it?

To answer that, it’s important to get a better understanding of what Round Hill is and what it does. It describes itself as a “full-service, creative music company with a core focus on music publishing”. It has a roster of new acts, but none of the songs in its substantial catalogue could be classed as blockbusters. Except, that is, the half-dozen early Beatles hits for which it owns the the US and Canadian publishing rights.

As well as royalty accounting, tracking and collection, Round Hill also offers music supervision and synchronisation (which means pitching tracks for use in TV shows, films and adverts), library music, the commissioning of original scores and the brokering of co-writes. It is this many-tentacled aspect that provides a clue as to why the business has bought the Offspring catalogue. And catalogue deals are more common than one might think.

“Trading in catalogue is par for the course,” says Gregor Pryor, co-chair of the global entertainment and media industry group at legal firm Reed Smith. “This one is getting press because of the numbers.”

Indeed, the history of the major labels is the history of the slow but steady acquisition of catalogues and smaller labels. Warner, for example, became pre-eminent in the 1970s after acquiring Elektra and Atlantic – and recently bought Parlophone, which used to sit within EMI. Most of EMI, in turn, has since been absorbed into Universal, which bulked itself up over the years by acquiring labels such as Motown, Def Jam and Island. Even independent labels are not shy of consolidation, with Rough Trade and Matador now sitting within Beggars Group.

Round Hill also needs to be understood as part of a new wave of independent companies such as BMG Rights Management, Kobalt and Concord Music Group. They all sit beyond the gravitational pull of the majors and big indies, focussing on building up large catalogues rather than nurturing new artists.

The Offspring catalogue acquisition, therefore, could be read as a statement deal by Round Hill, intended to send out a message to the rest of the record and publishing industry that it has very big plans for the coming years. It would be easy to laugh at the idea of the Offspring as a prize scalp were it not for two important considerations. First, the Offspring are just the starting point. Second, the deal covers two sets of rights – sound recording and publishing – and this is hugely significant for synchronisation.

“If you buy the masters and the publishing together, you clearly have an eye on synchronisation,” Pryor says. “Sync is the Holy Grail for lots of heritage acts and rights owners. Sync deals are an incredible growth area.”

Often in sync deals, the licensee has to negotiate a fee and term with a label and then do the same with the publisher. If one company can offer both rights in one deal, that becomes much more attractive on a business level, as well as being much easier in practical terms.

“There is always competition for these kinds of catalogues,” Pryor says. “Catalogue trading is like the subterranean world of the music industry. It’s an annuity business. You buy a catalogue and you have a really good idea of what it’s worth, or what money it can generate, as you can see the past returns. All you have to do is figure out what you think that asset class is going to be worth.”

What this means is that Round Hill will have done its due diligence on the Offspring’s catalogue, ensuring that it owns it all outright but also dispatching teams of accountants and lawyers to fine-comb their way through all retroactive royalty payments. From those, they can work out what is termed a “multiple”, forecasting what it will earn in the coming years.

In a statement after the deal was announced, singer Dexter Holland said: “We felt that having the right caretaker for our catalogue … is incredibly important to the future of our career. Round Hill understands that we are continuing to perform and record and that the visibility of our past is critical to our future.”

The corporate tone of the statement may seem more suited to a Silicon Valley start-up acquisition than a punk band, but it’s clear that the Offspring are in line for an ego boost. With Round Hill, the band will find themselves a priority again, more than a decade after their sales started to dry up at Columbia and newer and shinier acts soaked up the attention they had once enjoyed.

As Pryor says: “I would imagine the band have some form of preferred interest in getting this type of deal because a business like Round Hill will give them much more love and attention than a bigger label that has a huge number of artists. Plus, the broader economy is volatile, but music catalogues [as an investment] are pretty stable.”

It seems unlikely the Offspring will be doing the next Bond theme or John Lewis advertisement, but you can expect Round Hill to be swinging into action and placing as much of their music as possible. And if it’s successful, it is easy to envisage more acts of a certain vintage deciding to look for a similar deal. The Offspring’s musical legacy might be slight, but their business legacy could prove to be grand.