Experts caution that much of the web’s traffic is manipulated, from app downloads and YouTube views, to ad engagement and Yelp reviews. (Monster Ztudio/Shutterstock)

Most of us know by now that we can’t trust everything we see online. But just how much of the internet is fake? It’s more than you might expect.

Fabricated content stretches far beyond just fake news, viral hoaxes and manipulated images, as experts caution that much of the web’s traffic is manipulated, too — from app downloads and YouTube views, to ad engagement, Yelp reviews and Amazon ratings.

Indeed, it appears that even the population of the internet itself — and the activity it generates — can’t be taken at face value.

So while people are right to be wary of what they see online, half of those “people” are probably bots anyway. In other words, fake users watching fake content. And considering the questionable nature by which views are often tallied, perhaps the view counts themselves are fake, too.

To a certain extent, all the metrics are fake.– Frank Pasquale, University of Maryland

According to Frank Pasquale, a law professor at the University of Maryland and author of The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms Behind Money & Information, this kind of manipulated web activity is extremely prevalent.

“To a certain extent,” he says, “all the metrics are fake.”

If that seems surreal, it should; metrics are the engine of the internet, after all.

When it comes to fake views, as much as half of YouTube’s traffic in recent years has been found to be bots. (Dado Ruvic/Reuters)

Quantified information — such as video views, product ratings and ad impressions — inform what we do as individuals, as well as how marketing dollars are spent.

As markers of what we value, what we find interesting or entertaining, and how long we spend engaged, if those metrics can’t be trusted, it can distort everything we understand about the online world. Like Alice in Wonderland, with her giant tea cups and tiny doors, size is suddenly an arbitrary factor — and ultimately useless.

The value of metrics

How has this come to be? As it is, advertisers pay for impressions.

This is a lucrative business for online platforms and those involved in selling ad space, considering that pretty much everything on the internet that users don’t pay for is powered by ad sales.

And those ad sales are driven by metrics.

Given how pervasive online advertising is, you’d assume there would be a demand for more certainty with regards to how metrics are generated. But there is very little transparency about who is engaging with ads — and if they’re even human.

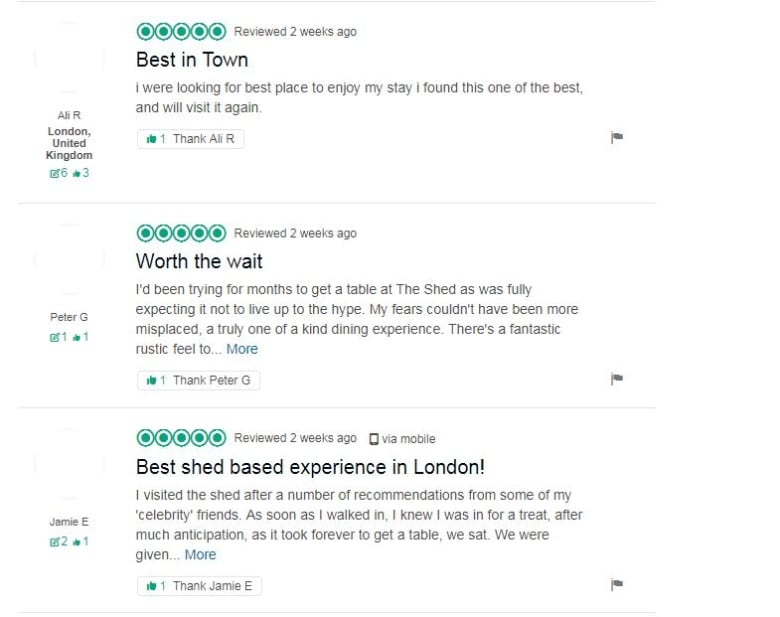

This is a sampling of some of the totally fake reviews that propelled a totally fake restaurant to the No. 1 spot on TripAdvisor in London. (TripAdvisor)

Meanwhile, as consumers, we use metrics to inform our decisions. Whether it is Yelp, Amazon or Facebook, we look at ratings and reviews to help us make our decisions about things like where to eat or what to buy. And when users are looking for a tutorial on YouTube, they’re likely to infer that the ones with more views are more popular — and thus superior.

But this can be dangerous, Pasquale warns, because “when something seems popular, it also seems trustworthy.” In this way, the same mechanisms being used to sell us products are also being used to sell ideologies.

“It’s not just agencies buying ads,” Pasquale said. “It’s also groups that are … buying themselves to the top of search results, so that viewers think their extremist messaging [is] a really popular or widely held view.”

For the most part, we’re blind to the mechanisms of how we come to see what we see online — or more generally, how things come to be popular, prevalent or appealing.

“Someone can bid two pennies more than someone else to be at the top of search terms,” said Pasquale. That can result in fringe groups buying the optics of legitimacy through a combination of fake views and purchased prominence

Indeed, when it comes to fake views, in recent years, as much as half of YouTube traffic has been found to be bots.

According to a report by bot-detection firm White Ops into a Russian operation called “Methbot,” this masquerade can be quite sophisticated, as bots charade as humans, moving a mouse around the screen, faking clicks, and logging into fake social network accounts.

Inside what have come to be referred to as “click farms,” rows and rows of unmanned smartphones play the same videos and download the same apps — all to bolster apparent interest.

So while it’s not like someone is hacking YouTube’s code to manually inflate video views, the view counts we see are no more representative of, well, what we would consider “real” views by real people.

These digital simulacra are the product of more than a decade of metrics-driven growth in which there’s been little regulatory oversight — and profit to be gained from inflating numbers.

“On one level, there is this winking alliance between the people at the platforms and the people in ad tech,” said Pasquale, who explains there are many related entities profiting off of too-good-to-be-true metrics — none of which are too keen to break the lucrative myth.

But according to some experts, the desire by bad actors to game the system through bots and other tactics will ultimately backfire.

Restoring trust

Each year, public relations firm Edelman produces an annual report called the Trust Barometer. According to spokesperson Sophie Nadeau, that research tells us that “fake metrics and engagement has the potential to contaminate the entire ecosystem in a way that’s bad for business, and bad for trust in key institutions like business, media and government.”

So what can be done about all of this fakery? Is it even possible to sort through the hype and deception? Or is it too late? Are we now mere tourists in a bot-filled world?

According to Nadeau, “it’s critical for business to demand accuracy of information, spend on quality, be agents for positive change in this area and advocate for transparency.”

-

AS IT HAPPENS

How this man tricked TripAdvisor into listing his shed as London’s No. 1-rated restaurant

- Fake online reviews: 4 ways companies can deceive you

For Pasquale, the solution is regulation.

“It needs to be illegal for companies to peddle false metrics,” he said. “There needs to be fines or penalties for gaming the system like this.”

Ultimately, the evident illegitimacy of so much of the web, its users and their supposed activity is the result of an over-reliance on automation and machine-driven efficiency, fuelled by greed and the desire for rapid growth.

“It’s an example of the failure of quantitative, automated metrics to take over the roles of human editors or gatekeepers,” said Pasquale.

If that’s true, he says the solution seems simple enough: If we don’t want the internet to be overrun by bots, it can’t be run by algorithms. It’s their digital world — or ours. If we truly want to take the internet back, he says, we need a lot more humans involved in online-vetting processes.

[“source=cbc”]