To drive the length and breadth of Saguache County, Colorado, is a dangerous undertaking. The roads, at least in spring, are lonely, clear and straight — “drive 30 miles then take a left” is the gist of most map directions. But the views are what can drive a person to distraction, veering recklessly over dotted yellow lines. There are hayfields drowned in water, blue and glassy so it looks like the sky fell into them, football fields full of black cattle standing stock-still like museum statuary, signs along empty stretches advertising meet and greets with the “Happy Gilmore” alligator, and crop planes that totter and swoop perilously over power lines before misting fields so green you think they might have invented the color.

The beauty of Saguache County can be an inconvenient one, though, particularly in the 21st century: It has some of the worst internet in the country. That’s in part because of the mountains and the isolation they bring. Saguache (sah-WATCH’) is nestled in between the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan ranges, a four-hour drive southwest of Denver. Its population of 6,300 is spread across 3,169 square miles 7,800 feet above sea level, but on land that is mostly flat, so you can almost see the full scope of two mountain ranges as you drive the county’s highways: the San Juans, melted into soft brown peaks to the west, and the Sangre de Cristos, sharp, black and snowcapped, thrusting almost violently upward to the east.

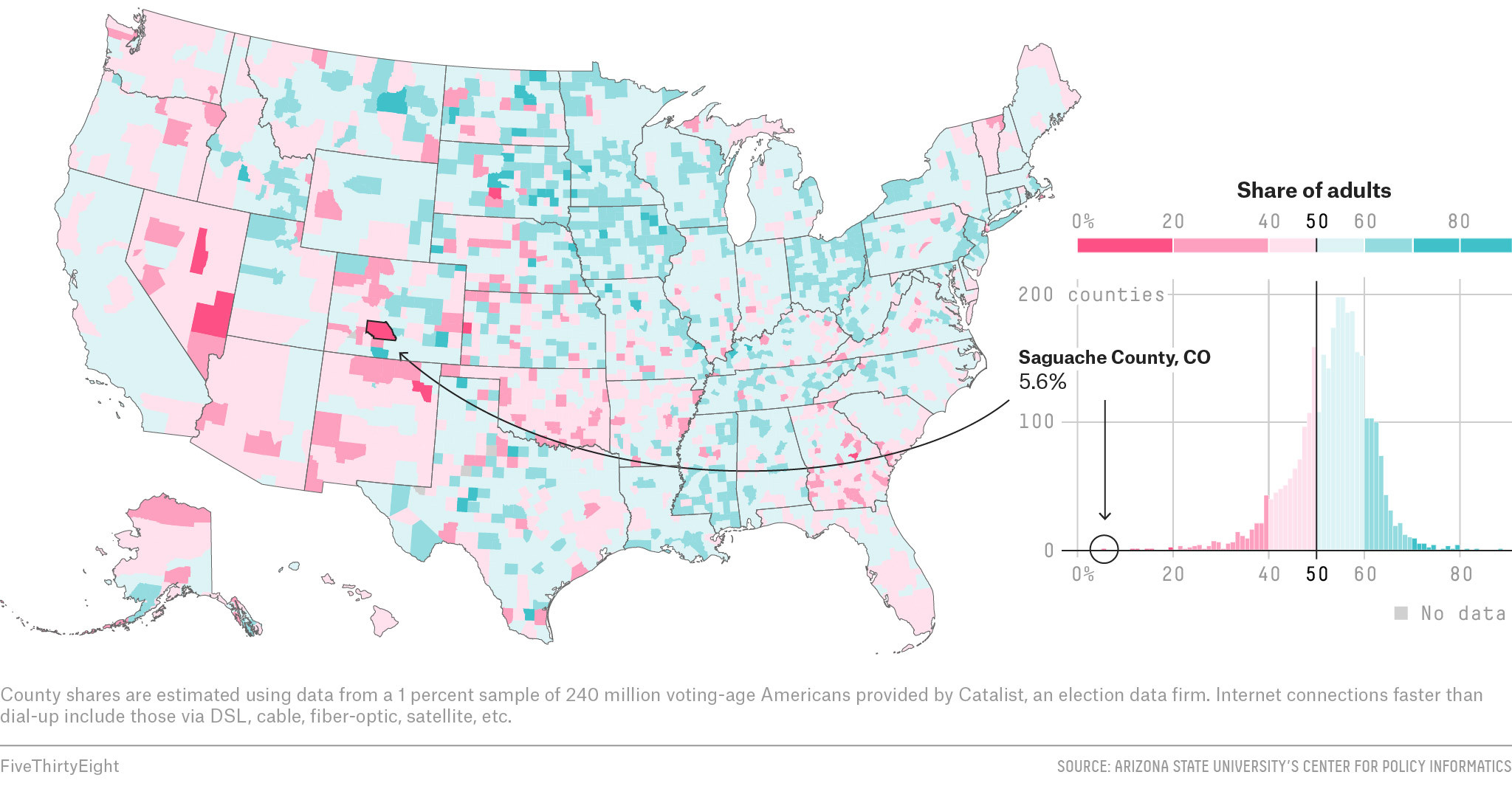

FiveThirtyEight analyzed every county’s broadband usage using data from researchers at the University of Iowa and Arizona State University1 and found that Saguache was at the bottom. Only 5.6 percent of adults were estimated to have broadband.

But Saguache isn’t alone in lacking broadband. According to the Federal Communications Commission, 39 percent of rural Americans — 23 million people — don’t have access. In Pew surveys, those who live in rural areas were about twice as likely not to use the internet as urban or suburban Americans.

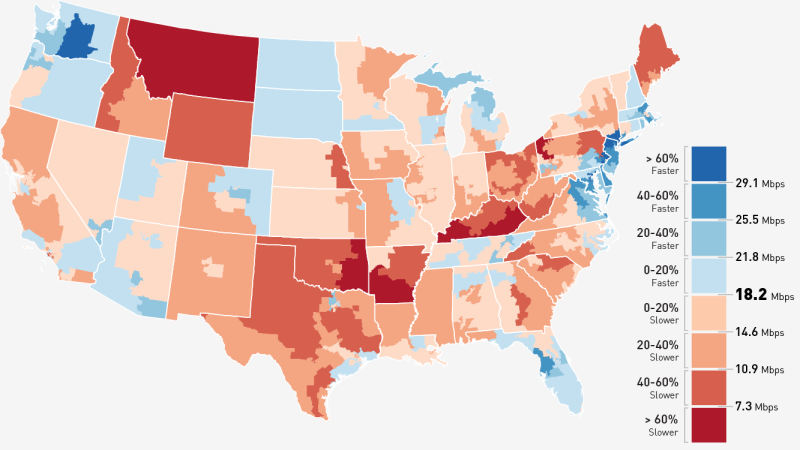

The FCC now defines broadband internet as the ability to download information at 25 megabits per second and to upload it at 3 megabits per second. This sort of connection enables a person to do the things that most Americans with home internet like to do — watch Netflix, play video games, and browse online without interruption even if a couple of devices are on the same connection. For around $30 a month, New York City internet providers offer basic packages of 100 Mbps service. In Saguache County, such a connection is rare; if a household wants a download speed of 12 Mbps with an upload speed of 2 Mbps, they can expect to pay a whopping $90.

This would be less of an issue if the internet weren’t so central to modern life. But taxes, job applications, payroll operations, banking, newspapers, shopping, college courses and video chats all are ubiquitous online. Saguache County’s students are expected to take their state assessments online even though an administrator at one school that houses K-12 students told me that until last year, the internet often went down for a couple of hours or even all day in the building.

The tide long ago turned from paper to digital in American life, and yet the disparities in access to the internet in parts of the country can be stark. Rural communities often face logistics problems installing fiber-optic cable in sparsely populated areas. In Saguache, internet problems are both logistical and financial; the county is three times the size of Rhode Island, while 30 percent of residents live below the poverty line.

Some would argue that the social contract has changed and that fast internet isn’t just a luxury — it’s a right of all 21st-century Americans. If that’s the case, we’re far from ensuring it. Just spend a few days hopping from town to town on Saguache’s long stretches of road.

Many people don’t have good internetEstimated share of adults with typical internet speeds faster than dialup, by county

The U.S. has a long history of trying to bring utility access to all Americans. In the early 1930s, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Rural Electrification Administration, 90 percent of American farmers lived without power. Many families could not access running water, heat and light for the home. The cost of running electric lines to the country’s most remote areas was prohibitive for profit-seeking businesses, but the REA found eager partners in rural electric cooperatives that had started to spring up in small communities with an eye toward modernization. The government began providing the co-ops loans to build out their electric networks, and by the end of the 1940s most farms in the country had power.

With clear eyes brought by 80 years of hindsight, it’s obvious that Americans should have access to electricity — the country’s economic and social well-being depends on it. Advocates of universal broadband argue the same could be said of fast internet. Already, the law says that all Americans should have access to internet services, thanks to the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which expanded the notion of universal service beyond just the right to telephone service. In 2017, many co-ops see bringing high-speed internet to the most isolated places in the United States as the 21st century’s answer to rural electrification.

Shirley Bloomfield, CEO of the Rural Broadband Association, says rural America should have fast broadband, in part, because it’s good for business.

She touted a 2016 study from the Hudson Institute that found that 66 percent of the economic impact of rural broadband went to urban economies rather than rural ones, given that many of the supplies needed to build these remote networks are sourced from urban areas. The same study estimated that if broadband was as good in rural areas as it is in urban ones, online retail sales would be “at least $1 billion higher.”

But there is also a less-quantifiable social good that fast internet access for all might bring to the country. Larry Downes, project director at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy and an internet industry analyst, said that by virtue of excluding some, the internet’s value as a network of connection was being diluted. “Any time we add one more person to the internet, we get that many more possible connections of people, so that has greater value.”

More pointedly: “The more you create second-class citizens, the more we just continue to see some of these political divides,” Bloomfield said. The last election was proof of a breaking point. “I think rural America kind of sat back and roared a little bit.”

The town of Crestone, Colorado, sits off state Route 17, at the end of a long road that cuts through scrub-filled land at the base of the Sangre de Cristos. When I pulled in one early morning in late May, I didn’t see a soul, so I browsed the local bulletin board — a wood stove for sale, a missing young woman, yoga classes — and passed a lot filled with yurts and something that looked an awful lot like a satellite dish. Crestone has become home to a certain kind of person, eager to live out of the 2017 mainstream, and the town is filled with spiritual retreat centers and transplants from out of state.

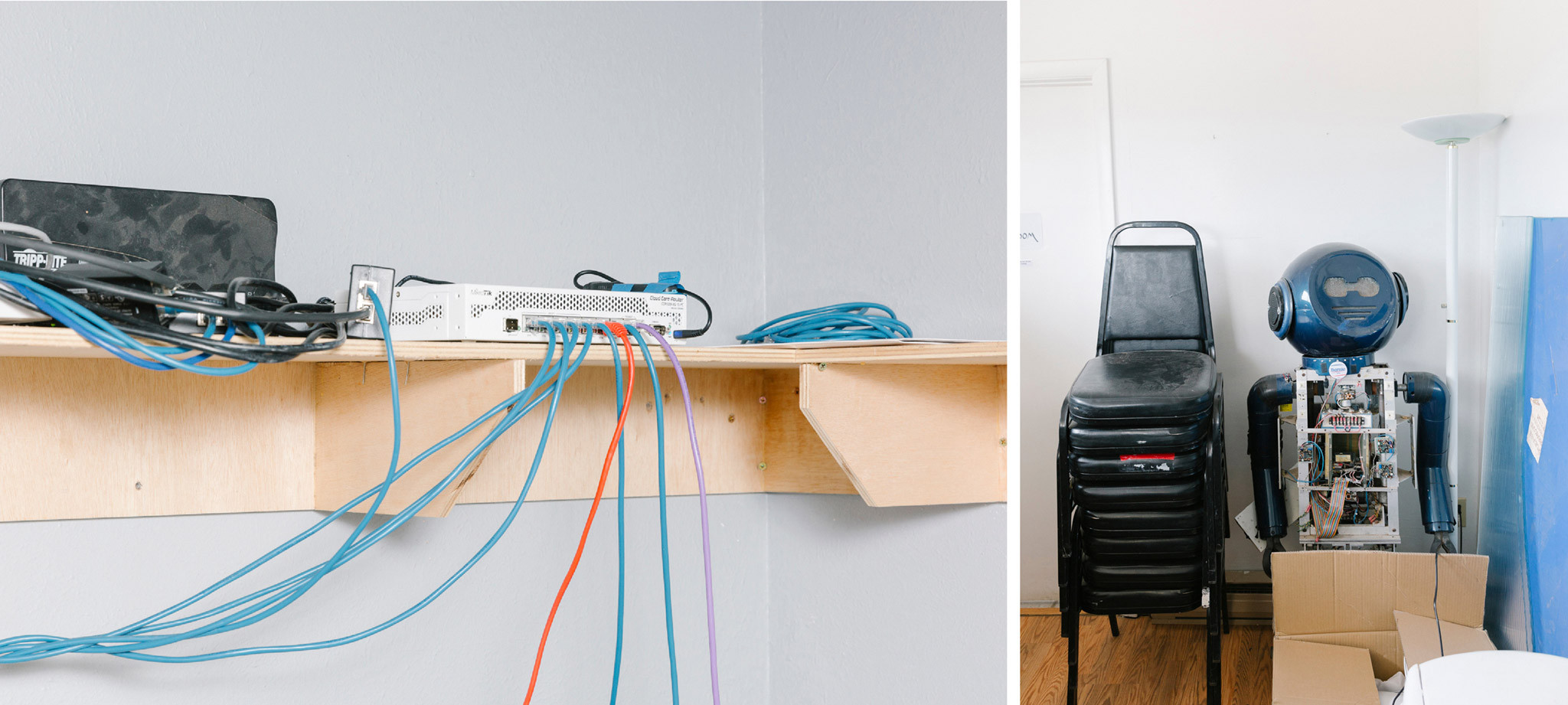

It’s also where Colorado Central Telecom has an office. The small operation offers internet and phone plans to residents in Saguache County and neighboring Chaffee County and has tailored its service to the needs of the more isolated internet user. While most urban and suburban providers use fiber cables laid in the ground, rural providers often use something called fixed wireless internet to avoid the installation of miles of expensive cable. When the office opened, a technician named Joshua showed me a back room filled with the same kind of satellite-looking dishes I had seen on the yurt. If a home wants Colorado Central Telecom’s service, the dish is attached to it and pointed in the direction of the nearest fixed wireless tower so that a signal can be beamed to the home. The dishes must be in the line of sight of the tower, which can get tricky if trees or other obstructions are in the way.

Maisie Ramsay, head of business development for Colorado Central Telecom, set out to show me over the course of the morning the kind of path that airborne internet signals must travel around Saguache County. From Crestone’s center we drove to a massive tower in a field just outside the town, then to a school in Moffat, a few minutes to the west, where a dish sat discreetly on the back of the building as kids played out front. The tour ended in the town of Saguache, at the northern end of the county, with Ramsay and I staring up at a tower on Cemetery Hill, a barren mound overlooking the tiny town. A woman named Pat Miller came out to ask if we were lost, and it turned out that she was a Central Telecom customer. “CenturyLink, you’ve probably heard, just was not going to give us the service,” Miller said, referring to the large telecom that services some parts of the San Luis Valley, where Saguache County is situated. “It was horrendous.”

This sort of complaint is common in Saguache County. In 2011, Ralph Abrams, the former mayor of Crestone, founded Colorado Central Telecom in direct response to poor service he said the town was getting from another large provider, Fairpoint. “Originally this started because Fairpoint was not providing more than half a [megabit],” Abrams told me. “Which is unusable,” Ramsay said. According to Abrams, the town was desperate for internet and the company was started because “none of the larger providers care about small rural areas.” Internet is a utility, Abrams said, and “utilities are a right for every person like road and sewer and water and electricity and we will bring it.”

Saguache County is a particular place. It’s still a bit cowboy-ish, though parts have an off-the-grid hippie feel. Its singularity of spirit means broadband can be a difficult sell to some. As one county commissioner, Tim Lovato, put it to me, “It’s kind of hard to carry a laptop when you’re on a horse.” It’s the sort of attitude that locals can brag about — a place that stands apart from the hustle and bustle of modern life — but one that others worry might hold back Saguache County in the future.

Lovato has lived in Saguache County his whole life. He grew up in a house with a wood stove and now lives in one with 32 big windows looking out on the mountains and a ranch that’s covered in chico, rabbitbrush and currant bushes. He drove me around one afternoon, pointing out his “girls” (cows), houses of people he’d known as a child, and prisoners from the county jail, out for their shackled afternoon constitutional in a residential neighborhood. Lovato, who uses internet only for emails and “maybe a little searching,” acknowledged that getting fast internet is important for keeping the county economically relevant, and yet over and over he expressed trepidation about what he called our “consumable world where everything is throwaway.” The internet seemed part of that to him, an immediate gratification machine.

At one point, I idly marveled that an old sawmill we passed, out of commission for decades, was still standing. “It’s not the internet, it’s not a renewable resource,” Lovato said in reply. The jump from sawmill to the internet took me by surprise, but it was as if Lovato was admonishing me for a mindset he perceived as out with the old, in with the new. Old sawmills, once gone, can never be replaced. A browser page will always refresh. The old things and ways of Saguache, he seemed to intimate, were in danger of being subsumed by a throwaway attitude if not for the vigilance of its residents. According to Pew, of the 13 percent of Americans who say they don’t use the internet, about a third — 34 percent — said that’s because they didn’t see its relevancy to their lives.

Saguache County is a place unlike many in the United States, which is why, for its residents, its particular way of life is so important to preserve. Charged with maintaining a connection to Saguache’s Wild West past is Dorraine Gasseling, director of the county museum and perhaps the country’s most blasé, delightful docent. Gasseling took me on a whirlwind tour of the county’s treasures one afternoon. The San Luis Valley was once a part of Mexico — Lovato and many other multigenerational residents come from Spanish-speaking households — so in the museum there were Spanish lace mantillas and statues of the Virgin Mary, but also prehistoric arrowheads, dueling pistols, playing cards, dinosaur bones and a rock marked “uranium” that made me a little nervous.

The museum’s pièce de résistance was the original county jail, famous for having housed accused cannibal Alfred Packer. “We had a ghost hunter here,” Gasseling told me. “He said we have 17 ghosts.” She made sure to point out that although the graffiti etched by prisoners had lots of girly pic drawings, there were no “nasty words, there’s no ‘G-D,’ no ‘F’s.” Back then, she said, “they had some manners.”

Reverence for the past is not an uncommon feeling in Saguache. Various people over the course of my visit happily said that things were done differently in the county and in the valley as a whole. “We’re in a time warp but in a positive way,” Kevin Wilkins, executive director of the San Luis Valley Development Resources Group, told me. “This is one place that hasn’t been Californicated or Disney-fied.” Joan Mobley, the former town administrator of Center — population 2,000 — said that most people pay their utility bills in cash and in person every month. “They come in here and it’s not just time to pay bills, it’s to socialize.”

But Wilkins worries that Saguache’s lack of broadband could spell a future decline. Rural areas in America as a whole are already having a tough time. They’ve suffered population decline in recent decades, but there was a particularly steep drop-off starting in 2006, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and rural areas are older than urban areas or suburbs. Rural America has lower labor force participation rates than the rest of the country because of its aging population. Marijuana grow operations have started to move into Saguache over the last few years, though that’s not the only kind of business that residents want to cultivate. Some people talk about the potential that broadband could bring, enabling small businesses, perhaps tech-based ones run by young people, to move to the valley to operate in a low-cost environment.

There are also more immediate needs to be filled. In health care for instance, Wilkins said, telemedicine consultations could provide residents with more and better health care options, which are crucial in sparsely populated rural America. Twenty-four percent of America’s veterans, a population with a growing need for mental health resources, live in rural areas. But, Wilkins said, “without robust connectivity, you can’t do telemedicine.”

“In order for rural areas to survive they need to overcome this lack of an economy of scale,” Wilkins said. And broadband is “the only way to bring [rural areas] parity to an urban environment.”

Rural electrification was a relatively swift process, spurred by government funds and a national movement to modernize the country’s infrastructure. But bringing sufficient internet to rural areas in the 21st century is slower and more piecemeal; small companies and cooperatives are going it more or less alone, without much help yet from the federal government.

There has been some indication that this could change. President Trump has proposed $200 billion in infrastructure spending, and with his recent statement that the spending plan would “promote and foster, enhance broadband access for rural America,” rural broadband advocates have some reason to be hopeful. But as of yet, there are no concrete plans for the initiative. Downes, who testified about broadband before the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee in May, said that there was “no discussion of when it’s going to happen, what it’s going to look like, where the money is going to come from, whether it’s going to be debt versus direct expenditures, whether it’s going to be government spending versus loans.”

The way the government implements spending and to whom it gives funds matters to smaller telecom companies like the ones in and around Saguache County. Currently, the San Luis Valley’s smaller internet providers that service its most remote areas are mostly frustrated by their interactions with the federal government.

“We applied, I want to say two years ago, for a grant that was broadband related and we did not get it,” Andrea Oaks Jaramillo, who works in economic development for the San Luis Valley Rural Electric Cooperative and Ciello, its related broadband venture, told me. “CenturyLink did get federal funding, actually, so everyone thought, ‘Oh yay, they’re going to do more things down here in the valley,’ and that has still yet to be seen.”

That frustration — that large companies are rewarded but don’t do the work in the neediest areas — is a common theme in the valley. That has led local companies to think creatively about their own plans. Colorado Central Telecom’s towers are beaming signals to local dishes, and Ciello is using loans from the San Luis Valley Rural Electric Cooperative and others to lay miles of fiber-optic cable in the hopes that the broadband venture’s fast speeds can be a competitive advantage.

Competition among providers is welcome to people like Mobley, Center’s former town administrator. “We’re trying to invite anyone and everyone,” she told me, “to drive down costs and make [the internet] more available.” Center is home to a large community of agricultural workers, and money is tight in the town.

In an ideal world, though, the government would step in to help implement a broadband plan, opening up possibilities for Saguache County’s towns and the San Luis Valley’s small internet providers.

When I asked Mobley how she hoped the federal government would deploy help on broadband should the Trump infrastructure project be financed, she said that free public Wi-Fi would help residents. There was already a need for it percolating in the community. “We had people sitting in the park after 10 p.m. at night and we were trying to figure out what they were doing — they’re not drinking,” she said. It turns out a company next to the park had recently opened and its Wi-Fi wasn’t password protected. The city told the company to password protect its connection, but it made Mobley think about whether that’s something the town of Center might someday provide to its residents. “There are people here that are looking for that free service.”

When I asked Abrams what he would look for in broadband funding from the federal government, he paused to consider: “Well, if the FCC would give funding to the small local people who know how to do it, I would say for a million bucks we could [provide broadband] in Saguache.”

Asked the same question, Wilkins of the San Luis Valley Development Resources Group said he would want to connect “anchor institutions” — hospitals and schools — throughout the valley, and that, “realistically, pragmatically, if the federal government would put up $10 million that we can leverage with creative financing and private sector investment and loans, that should help us accomplish the goal.” Downes and his research partner Blair Levin, who helped write the National Broadband Plan of 2010, have recommended that $20 billion be set aside nationally for a “one-time rural broadband acceleration program” that would, as Downes put it to me, “make it possible to provide broadband to all the current census tracts where it doesn’t exist at all today.”

Even if broadband funding and access arrive in Saguache County, there still will be cultural hurdles to overcome: the view that certain groups in the San Luis Valley don’t need a connection. Wilkins wondered if all residents needed home broadband, or just some. “You’re looking at Center School — look at the percentage of Latino, look at the percentage of farm worker. What do they need broadband for? To watch Netflix?” I pointed out that the kids in such households might need the internet to complete their schoolwork. Wilkins countered with cost. “If I’m making $20,000, $30,000 a year and I’ve got three kids, $100 a month [for internet] might be whether [or not] I provide dental care for my children.”

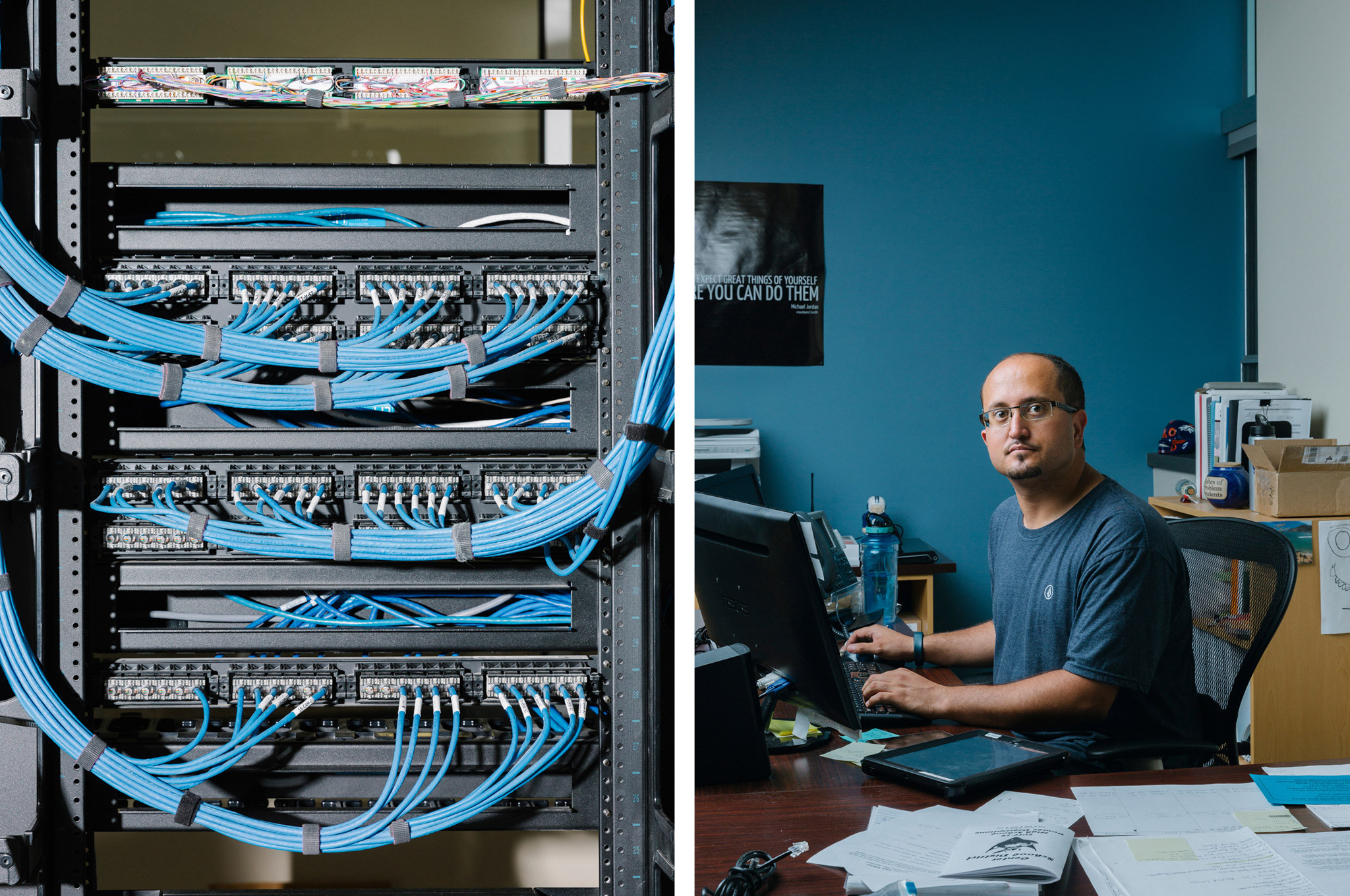

To Julio Paez, though, a Center native and the Center school district’s information technology director, broadband access and students’ exposure to technical knowledge is crucial to their future. Most students’ summer jobs, Paez said, involve doing “back-breaking work” in the fields. “I’m speaking from a personal point of view: It motivates them more to say, ‘I want to do something better, I want to continue my education and get a good career.’” In high school, Paez got a job helping the school IT director, then left Saguache for a few years to go to college. When he came back, Paez said, “I continued the tradition of hiring students.” This summer, there are four helping him prep computers, iPads and other devices for the upcoming school year.

These unforeseen serendipitous opportunities — summer jobs that become careers — are what motivate the county’s small internet providers to continue to pursue broadband as a public good. For now, no one in Saguache County is counting on a deus ex machina of funding from the federal government that turns universal broadband service from fantasy to reality. In real life, the practicalities wear.

“I’m tired,” Abrams told me, “of being the David to everyone else’s Goliath.”

[“Source-fivethirtyeight”]